The ADA’s 2016 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes recently shifted its language to match the ADA’s position that diabetes does not define people, “the word ‘diabetic’ will no longer be used when referring to individuals with diabetes in the ‘Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes.’ The ADA will continue to use the term ‘diabetic’ as an adjective for complications related to diabetes (e.g., diabetic retinopathy) (54.)'” This means that “diabetes” is now used to refer to the person who has it, instead of “diabetic;” for example, “My sister has diabetes,” not, “my sister is a diabetic.”

The name shift seems simple, but it’s packed with emotions, implications, and for some, even anger. I wrote a piece, Diabetic v. Diabetes, shortly after the ADA published the 2016 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes, which explained the name change. When I linked to the article on Semisweet’s Facebook page, within seconds, the first comment was, “This is stupid.” Beyond Type 1 featured the article, and it garnered some healthy debate on the Beyond Type 1 Facebook page as well.

Some people see diabetic v. diabetes as splitting hairs or unnecessary political correctness. When I encounter the people who prefer to be called “diabetic,” or at least voice a strong and angry opinion against those asking to be called, “person with diabetes,” I respect their right to be called “diabetic.” In general, it seems these people have lived with the disease for many years— years when the battle was greater because technology wasn’t as advanced and understanding was scarer. Usually, these people are adults; however, children are more sensitive to language, labels, and their implications. In fact, we’re all probably not too far removed from that hateful comment or name someone hurled at us on the playground.

I’m the parent of someone who has diabetes. I couldn’t protect my son from getting diabetes, but I can try to protect him from the implications of being called “a diabetic.” He’s not even in kindergarten yet, and already kids his age have told him he, “can’t eat a certain food because [he’s] diabetic.” He’s been told he can’t play a certain sport because he’s “diabetic.” A neighbor kid didn’t want him in her yard because he’s “diabetic.” He’s brought home treats, like half a muffin or cupcake, from school because he didn’t eat it when the other kids did. We don’t make certain foods off limits, but he’s heard kids his own age tell him what he can’t eat. I wonder what he’s thinking as he watches his classmates eat their treats. He can eat that cupcake or cookie because he has diabetes, but he’s inherited the stereotype that he can’t, because he’s “a diabetic.”

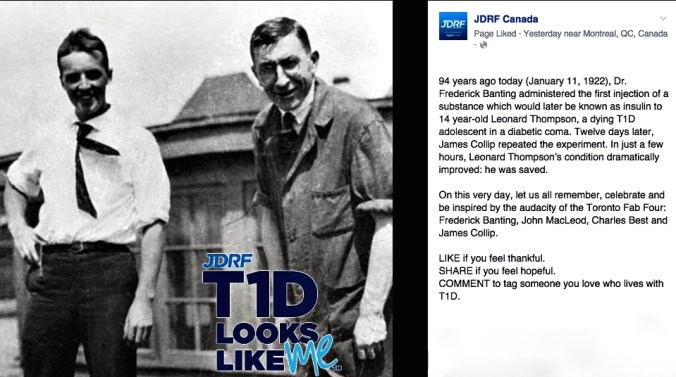

The governing associations like American Diabetes Association are changing their language, and I think this is because our perception and understanding of diabetes is changing. To be “a diabetic” was a certain death sentence 94 years ago. After insulin, to be “a diabetic” meant doctors predicted vastly shorter lifespans; fear and misunderstanding from teachers, relatives, and the larger medical community impacted people’s lives negatively. Women with T1D were told they could not and should not have children (case in point, Steel Magnolias).

In this era of better treatment, people with diabetes can live normal lifespans with fewer complications. As more and more people live longer and better with T1D, we’re starting to understand that living with a chronic disease or condition, like diabetes, has impacts on our emotional health, romantic relationships, and mental health. Having diabetes, means we can talk about this, and if we talk about being “diabetic” versus living with diabetes, there’s a simple paradigm shift at work: a limited life vs. a limitless life.

In images, the paradigm shift looks like this.

Below is the picture of a child who’s just been given a shot of insulin for the first time in 1922, and he’s starting to wake up from DKA. He was in a Canadian hospital with a ward for diabetic children. Just weeks before, his parents sat at his literal death bed.

photo source: Library and Archives Canada

He’s a picture of 4 time Olympian, Kris Freeman. He happens to have Type 1. In the photo, he’s training for another race and is wearing an insulin pump, Omnipod, on his arm.

photo source: http://krisfreeman.net/

In both pictures, we can see the life that insulin makes possible, and what’s harder to discern, but still visible, are the implications of being diabetic versus having diabetes.

Being diabetic once meant limitations, and yes, having diabetes requires my son to make sacrifices and take extra steps, but being a person with diabetes puts the focus on personhood. Thankfully, we’re living in an age when having diabetes means it’s a conversation about what we can do instead of what we can’t, and that’s ultimately the difference between diabetes and diabetic.

This is another example of someone in the fitness community not understanding that type 1 and type 2 are different diseases. To Vinnie Tortorich’s credit, he’s now educating himself on the fact that type 1 is an autoimmune disease and is unrelated to lifestyle and diet,

This is another example of someone in the fitness community not understanding that type 1 and type 2 are different diseases. To Vinnie Tortorich’s credit, he’s now educating himself on the fact that type 1 is an autoimmune disease and is unrelated to lifestyle and diet,